Why This Painting Costs $1000

by Lorette C. Luzajic

I find it amazing and amusing to watch art collectors bid ridiculous sums like 100 million dollars to own a Van Gogh or Modigliani painting. It would be difficult to buy a museum or a mansion or an aircraft for such a price, but some old cardboard doodled on by someone long dead is literally worth someone’s fortune.

A Jean-Michel Basquiat painting is going up for auction next month and is expected to fetch 40 million dollars!

Untitled, by Jean Michel Basquiat

Most art doesn’t cost anything close to these amounts, but the price tag can still be a sacrifice. Even wealthy collectors don’t have unlimited thousand dollar bills to toss about for every artwork that strikes their fancy. Folks who are working with a limited budget for art, or who want to start a collection, often wonder how a mid-sized painting can cost so much.

Some artists are offended by the question. “Why does this painting cost $1000?” I see it as an opportunity to explain how much goes into an artwork behind the scenes.

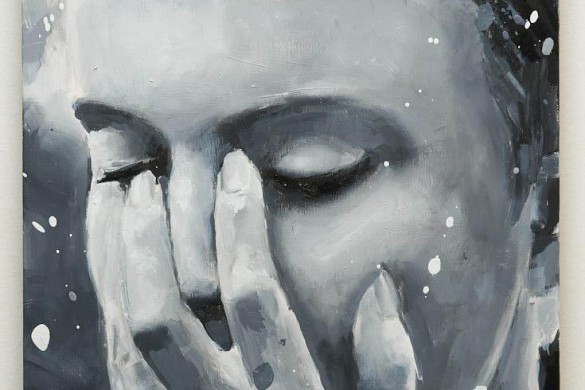

Let’s consider a 30×40” piece I finished recently called The Reflecting Pool. Every artist prices their works differently. For myself, I find it simplest to price by size. Size is not always a fair indicator of time or value, but I’ve determined that for me, it’s the best system. Currently, all of my paintings of this size are $950.

The Reflecting Pool, by Lorette C. Luzajic

The half and half rule

A thousand bucks is a beautiful chunk of income that can cover a city girl’s rent or a plane ticket overseas or someone’s car insurance, parking, AND repairs…but always remember the half and half rule.

Half of the ticket price goes to the artist and half to the dealer, gallery, or venue. Sometimes commission is only 30% and sometimes it’s as high as 60%, but half and half is most common. This dramatically reduces the total for this work to $425.

Many of you have grumbled about this on my behalf, upset at how artists are robbed of their due. Well-meaning family members and friends understandably want the full ticket proceeds to line my pockets. Artists, or course, notoriously bicker about this injustice until they are blue in the face.

Please understand that I do not share this outrage. I appreciate where it’s coming from, but the fact is, it is our dealers and venues who find people to look at our work.

No one would know to ring my actual or virtual doorbell and stop by to see what I’ve got if all of these galleries, museums, cafes, and agents were not working tirelessly to put our names out there.

Selling art is the most honourable part of this game, and the most difficult. There are millions of people making art and only a few interested in selling it for us. Real estate for wall space is incredibly expensive. Wine and cheese for opening receptions, time and materials spent on promotion, venue repairs, website and other operational costs plus some kind of wages all add up to astronomical. Yes, I do wish I could keep the 100%. But it wouldn’t have sold at all if those working on my behalf didn’t show it to anyone. We need to start praising our sellers for the risks they take for the sake of the passion of art that we share.

“How long did this painting take you to make?”

“Five hours,” I answered the last time I was asked this question. It was a small sized work priced to fly off the walls at $250, and happened to be one of the works that came together quickly. I could see the calculations going on in the woman’s head. Was I worth fifty dollars an hour?

Recalling the half and half rule would bring it down to $125, only $25 per hour, not bad, still twice the minimum wage!

For The Reflecting Pool, a very freestyle abstract piece, the outcome was a little bit different. This painting was underway for well over a year. It’s impossible to say how many hours were spent on it- sometimes I pull out an unfinished work and spend an afternoon on it, other times I dabble a bit on it every day until it works out, other times I work for weeks or months on something and it never comes together at all.

The amount of time it takes to make a painting always includes the amount of time it took to make numerous other paintings that didn’t make the cut. Even if this painting took just the day, it actually took 43 years.

All the experimenting, practice, and development over the years results in pieces that are discarded or given as gifts to Aunt Matilda, not just the ones that end up showing in a gallery. The process and progress reflected in new works was not realized in the five hours of any one particular piece, but in a lifetime of stops and starts.

Materials fees

Besides labour and inspiration of course, are material fees. The canvas I like best for this size work is from 30 to 60 dollars. An artist could paint on paper, found wood, foam core, or other cheaper items, and sometimes I do. We all have preferences for the kinds of substrates that work best for us, and this is mine. This work also used acrylic paints, spray paints, paint brushes, paint spatulas, gouache paints, inks, oil sticks, oil pastels, etc. etc. etc. Depending on the demands of an artist’s style, and their personal preference for how a product performs, paints and brushes both range from $2 to $50 each on average.

Unsold works

So far, we’re talking completely theoretically, because this work is unsold. And there are about 80 unsold works circulating venues or sitting in my studio. That’s several thousand dollars just in materials, never mind the time. This is necessary, because artists have works circulating at multiple venues, and must also be ready to exhibit more if a proposal is accepted or an invitation comes.

Hidden fees

Every business has fees that the consumer or audience doesn’t see. But these fees are not hidden from the artist! Our expenses list is much longer than time and materials. Entry fees, hanging fees, studio space fees, rent or mortgage, venue rental fees, cooperative fees, membership fees, education fees, transportation and shipping fees, transit or car fees, table fees, website fees, maintenance fees, education and course fees, fair or event fees.

If we show a painting in another city, it can cost $25 to $100 to ship. If it doesn’t sell, that doubles upon return. Showing a piece overseas could cost $2000 in shipping! Artists priced below $5000 aren’t usually showing yet internationally on a regular basis. When you see living artists with price tags of $20000, it reflects these enormous costs. To take 30 works plus one’s self to an overseas fair could cost fifty grand.

Local fairs are a real bargain. A table or booth at a local arts event can be $25, or, if you are lucky enough to be accepted at The Artist’s Project, it’s three grand for the weekend. That’s right, three grand.

Many shows, grants, and fairs also charge a submission fee- that means we pay money just to be considered. If we are accepted, we might pay a hanging fee towards the venue rental, in addition to the half and half rule, if the item sells. This sounds harsh, but the reality is, venues need to find ways to stay open and to be able to more forward with programs. Nothing is free. At most fairs, the artist keeps 100% of their sales, but as we saw above, the cost of inclusion is mind boggling.

Last, but not least, prices must go up throughout one’s career.

It’s inevitable that prices of an artist’s work must go up over the years, to keep pace with inflation and the economy, as well as to reflect their professional development. This is terrific, except for the caveat that the price cannot go back down.

I might very much want to be able to sell this piece to a friend or to a collector on a budget for a few hundred dollars- after all, any artwork that moves out of my studio gives me some cash flow for new materials and more space. It might be worth much more, but any amount of money helps. Some stock is “dead” – I no longer feel it reflects my best creativity, or I never did- or it does, but few artists are selling so many pieces that there aren’t many great works left behind. We might want to sell these ones off for a song and dance, but we can’t. Once a price is determined, we can’t go backwards.

Think about it. It’s not fair to our art dealers or collectors if we sell one for full price and someone else gets it for a third of the price.

Sometimes, we’ll have “yard sales” privately, some kind of clearance in order to make room, and we can use these promotions as special events to bring attention to our practice. But we must be very judicious about this. A diamond store can have a holiday sale, for example, but if the diamonds there were always on sale, they would no longer be worth the regular price. If the $1000 diamond necklace was always sold for $400, or the special sale price of $400 happened once a week instead of once a year, the value of the diamond would become $400 instead $1000. It’s no different with our paintings.

So there you have it, why this painting costs $950 dollars. Now you know that it’s a steal.

Lorette C. Luzajic

Contact Carrie Shibinsky if you would like to purchase The Reflecting Pool. [email protected]

Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto based writer and an artist working in collage, paint, and photography. She is a journalism graduate and an independent, lifelong student of art history. She is editor of The Ekphrastic Review: writing and art on art and writing, and also writes a Wine and Art column for Good Food Revolution. Her latest poetry book, Aspartame, is a collection inspired by various paintings. Visit her at www.mixedupmedia.ca.